Lalibela, Ethiopia’s site restoration project, “Conservation action plan for the rock-hewn churches in Lalibela. Monitoring System for Biet Gabriel Rafael “

UNESCO and WMF have launched a Lalibela safeguard project. The project is entrusted to IPOGEA team leader Pietro Laureano and was carried out in collaboration with the Department of Construction and Restoration at the University of Florence for Structural Studies and the University of Cape Town for the GIS survey. The project has operated according to an integrated operational strategy involving cognitive aspects and pilot interventions. The Lalibela site, in fact, constitutes a complex system of which the churches are the highest known and monumental aspect, but are only part of an overall urban and territorial design of great interest to be interpreted.

Of this overall design are an integral part:

1) the imposing traces of moats, open and underground channels;

2) archaic structures in stone blocks, rocks, and hypogeals, witnessing the long-term historical stratification;

3) the set of traditional dwellings whose presence makes the site still vital and establishes a continuity between the ancient past and the current inhabitants.

The ultimate goal of the project is to ensure long-term protection of this set of values by guaranteeing local management and maintenance capability. This is possible through the understanding of the urban environmental system and the identification of all its components. Rebuilding the way that, for example, protecting the city from rain and ensuring drainage, it is possible to avoid the use of external protections such as shelter. One of the goals of the project is to find solutions that allow the removal of shelter from the churches by restoring to the landscape its original appearance by guaranteeing waterproofing and drainage with traditional technologies that can be realized by the local workforce. In this perspective, the project has operated in two directions the cognitive and operational level.

The cognitive level has allowed:

The identification of the historical stratification of urban, architectural and monumental structures through the analysis of the typologies of the rock and the identification of the temporal process of progressive deepening of short and moat;

The diagnosis of the structural vulnerability of the monuments and the geometric knowledge and the cracking of significant cases through a sensor monitoring system.

The operational level has achieved:

A pilot and training site for the reuse and experimentation of local muds that are breathtaking and suitable for the waterproofing of monuments;

The experimental cleaning of a moat to ensure drainage and low moisture protection and restore water collection tanks.

The actions have allowed us to outline the integrated restoration strategy to be implemented on different scales:

Monumental, operating the structural and architectural restoration of churches;

Through the recovery of ditches, water management systems, tunnels, underground pathways, soil protection and ecosystem preservation;

Urban, through a visualization and valorization of the entire historical city with its paths, gates, residential areas and civil spaces;

Urban management and social management through the preservation of traditional habitat through restoration and functional adaptation, especially to water and sanitation services, to ensure populations and incentives to architectural maintenance.

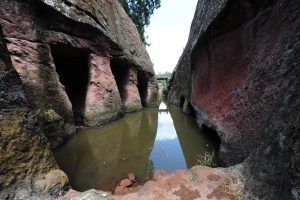

The pilot site for cleaning drains

The degradation of monuments due to water is not just that determined directly by the rain. Since the structures are hypogee, digging lower than the plane, the courtyards and underground rooms tend to collect water that, if not drained, attacks and erodes the monuments from below. To overcome this phenomenon Lalibela was provided with a mighty moat system that drained the courtyards of the monuments, tunnels, and underground rooms while keeping them dry. The system also served to convey water into tanks and irrigate the gardens, transforming a possible danger into an indispensable resource for the entire community. Over time, maintenance of these structures has caused clogging for deposits formation and moisture stagnation. The study found that the deep north courtyard of Biet Gabriel Rafael, where a deep cave was dug, was probably drained in the past by the huge ditch in the West completely blocked by sediments. Large open cavities are opened in the moat and traces of bulkheads and water control devices have been identified. It was therefore assumed that the moat would act as a further large reservoir of the complex and excess wastewater disposal system. This has been done for the cleaning up of the moat sediment that did not have interest in archaeological stratification since deposited in recent years. The cleanup of the work confirmed the hypotheses. The moat drains the excess water and keeps the court and the monument dry. During the rainy season it has retained water right in its lower part revealing the ancient tank function. In fact, the inhabitants have now resumed using it by going to catch water.

The pilot site for the detection of mortars

The main reason for the degradation of the Churches of Lalibela is the infiltration of rain water that motivated the installation of roofs. The covers, however, do not guarantee rain protection from rain, create environmental protection problems, do not ensure proper water disposal and damage aesthetics and landscapes. Church roofs in the past were protected by a grid system, mortar application, and constant maintenance. The purpose of the pilot site was to rebuild this knowledge by identifying locally available methods and materials available to the local population. Breathable, waterproof and remarkably strong plasters were found in local architectures and cisterns. Experimentation has been the composition and processing of these mortars with a team of local operators who have been trained in their preparation and commissioning. Several types of mortar have been produced and tested on specially designed sample surfaces. Pigments with the same local rock were added to the mortar to obtain a color and texture identical to that of the monuments. The engineers and the workforce have undergone the different sample surfaces to stress and watering tests, and the compounds and procedures that give the best results in local conditions have been identified. The technique has proved to be suitable for roofing of monuments, easy to apply and reversible. It allows the permeability of structures, protects them and does not show any visual disturbance since at the level of the whole it camouflages completely with the material, the color and the original texture of the roofs. It is completely reversible and can be applied at very low prices. Especially being handled locally, it ensures the constant control and maintenance required to ensure long-term protection.

Graphic reconstruction of the Lalibela site.

A) The site in the hypogeum phase with the first digging of the moats.

B) The insertion of basilic structures with the consequent digging of orthogonal cores and the deepening of the moats.

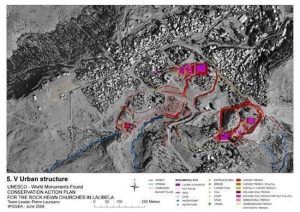

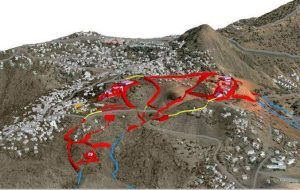

The urban structure. Locating the moat weave re-emerges from Lalibela’s urban shape. Not just a set of monuments, but a city with homes, gates, fortifications, deposits, water collection and irrigation systems.

We are used to reading the shape of a medieval city from the traces of its walls. In the hypogeal city of Lalibela where everything is the reverse of the usual is the ditches to identify urban space. The harmonious Lalibela urban design appears in the table through the three-dimensional highlight of the ditches, perfectly integrated into the environment.

Biet Gabriel Rafael in the context of the Eastern Group. Planimetry.

The western moat of Biet Gabriel Rafael, with water, following the cleaning.

The pilot site for the detection of mortars.